Robb Report

September 2002.

It began as boxes within a box. To be precise, 35 boxes of what Fredi and Robert Consolo modestly call their “accessories” had to find a home within a contemporary box – a penthouse overlooking Miami’s neon-blue Biscayne Bay. What emerged is a glamorous interior in the profoundly appropriate Art Deco style.

Swathed in glossy paneling and mohair upholstery, the penthouse is a cocoon of luxury. With it’s fluid, rounded shapes, the living room’s clubby arrangement hints at the opulent fabrics and exotic woods that distinguished French Art Deco of the 1920s. From the bold palmettes on the glass entry doors to the vibrant banana leaf-patterned carpet, the geometric motifs of Art Deco are alive and kicking, much as they have been since the early 1920s, when Henry Hohauser and other architects put the fledgling resort on the map.

It is no coincidence that everyone involved in the project has roots in South Florida. “If you’ve spent a large part of your life in the Miami area,” says architect William C. Taylor, a fifth-generation Floridian, “you can’t help having an affection for the Art Deco style.” Interior designer Phyllis Taylor, the other half of the husband-and-wife team, grew up in New York and Miami. The Taylor & Taylor Partnership’s offices are located in the heart of Miami Beach, home of the largest Art Deco district in the country. Fredi Consolo’s grandparents lived in South Beach.

“To me, Art Deco is the most romantic style, and the emotional connection with my grandparents was certainly a part of it,” she says.

“ Our house in Miami seemed too large and too formal to accommodate Art Deco,” Fredi adds. “But this apartment on the 31st floor seemed New Yorky and glamorous, the perfect setting.” Having found the right design team for her vision, Fredi started removing from the boxes all her treasured objects, which had been scattered between the couple’s Miami house and their Asian-themed second residence in Montecito, Calif. (Robert Consolo owns the Tuscan Greyhound Park in Arizona.)

“ I asked Fredi to take everything out and photograph each piece separately,” recalls Phyllis Taylor. “That gave me a giant jigsaw puzzle to work out.”

What emerged were Lalique perfume flacons, bronze sculptures, and light hued French side tables from the 1930s and 1940s. One favorite piece, a palisander sideboard and suede-inlaid game table by Jules Leleu, was added later. Phyllis Taylor says she relished “going to the ends of the earth” to find the perfect pressed-glass sconce or nickel-plated torchere.

“ Fredi was worried that her art, mostly modern and contemporary paintings, would cause a jarring note,” says Phyllis Taylor, who had no problem placing Mark Kostabi’s Tispy over the bar, a Miro watercolor over a 1928 French console, and a Louise Nevelson totem at the living room window. “I knew it would add spice.” It was the artwork, in fact, that suggested the room colorations – yellow and gold for the dining room, a subtle green for the bedroom, honey tones for the living room.

Meanwhile, Bill Taylor indulged his love of architectural history. He had to defy the existing architecture, whose worst flaw was the dearth of exterior walls. “The walls were all glass, protected by a white grid.” Says Taylor, who diverted attention with the same rich wood paneling used on the Normandie. In fact, the ship’s Grand Salon, the largest and most lavish public space afloat when the ocean liner steamed into New York harbor in 1935, became the inspiration for the dramatic “fins” that enclose the dining room.

“ The ceiling was 40 feet tall, with artificial light flooding in over the columns from ceiling and wall fixtures,” Taylor says. “The fins that separate the dining room from the foyer, yet keep it open and light, serve to accentuate the verticality that is an element of Art Deco. The Normandie’s columns were finished the way my fins are, though I simplified that caps and bases.” Light washes down from a raised soffit, illuminating the anigre panels that were chosen for their subtly rich grain and then meticulously matched.

The stepped ceiling cove also marks a “streamlining of the elaborate details of the past century.” Says Taylor. The cove brings the tall penthouse ceilings into human scale, while adding the requisite dollop of glamour. The dining room’s circular plaster ceiling medallion also plays on the Deco geometry.

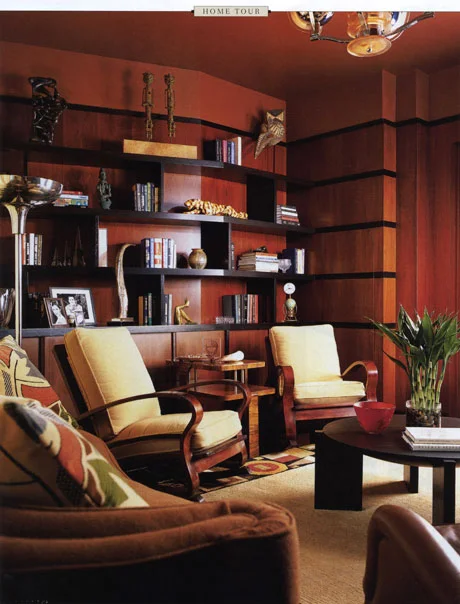

The streamlined ziggurats, another signature motif of that era, add interest to walls “that had very few right angles,” says Bill Taylor. “We had to bring some convention to an unconventional plan.” The ziggurat makes useful appearances in the master bedroom, with its parchment grid inspired by Jean-Michael Frank, and in the cherry-paneled library, with its collection of African tribal art.

Most of the new upholstered furnishings are deeper and higher than their Deco predecessors. Biedermeier style bar chairs are deliberately substantial, as are the dining chairs by Donghia. “The couple’s late 1930s wood-trimmed armchairs are unusually cocooning, though low slung,” notes Phyllis Taylor. The living room carpet’s geometric pattern is of local flora, to give ‘Radio City gone tropical,’” says the designer.

All of which fits in with Miami’s heritage and its exuberant attempts at polish and sheen. “We pulled out all the stops to make it work,” says Bill Taylor. :Art Deco was the inspiration in those boxes, but we added a stamp of creativity.” Thinking out of the box, indeed.